In university space planning, every square foot is valuable.

Contents

Challenge #1: Measuring your space utilisation rate (and getting others to understand what ‘good’ looks like!)

The challenge:

Perhaps your current figure has sat in the ‘fair’ band for a number of years, and it looks to senior management like progress isn’t being made (when you know it is!)

We’re tackling this first, because even if your current space utilisation rate is actually pretty good, getting senior management or other colleagues to see this can be a job in itself.

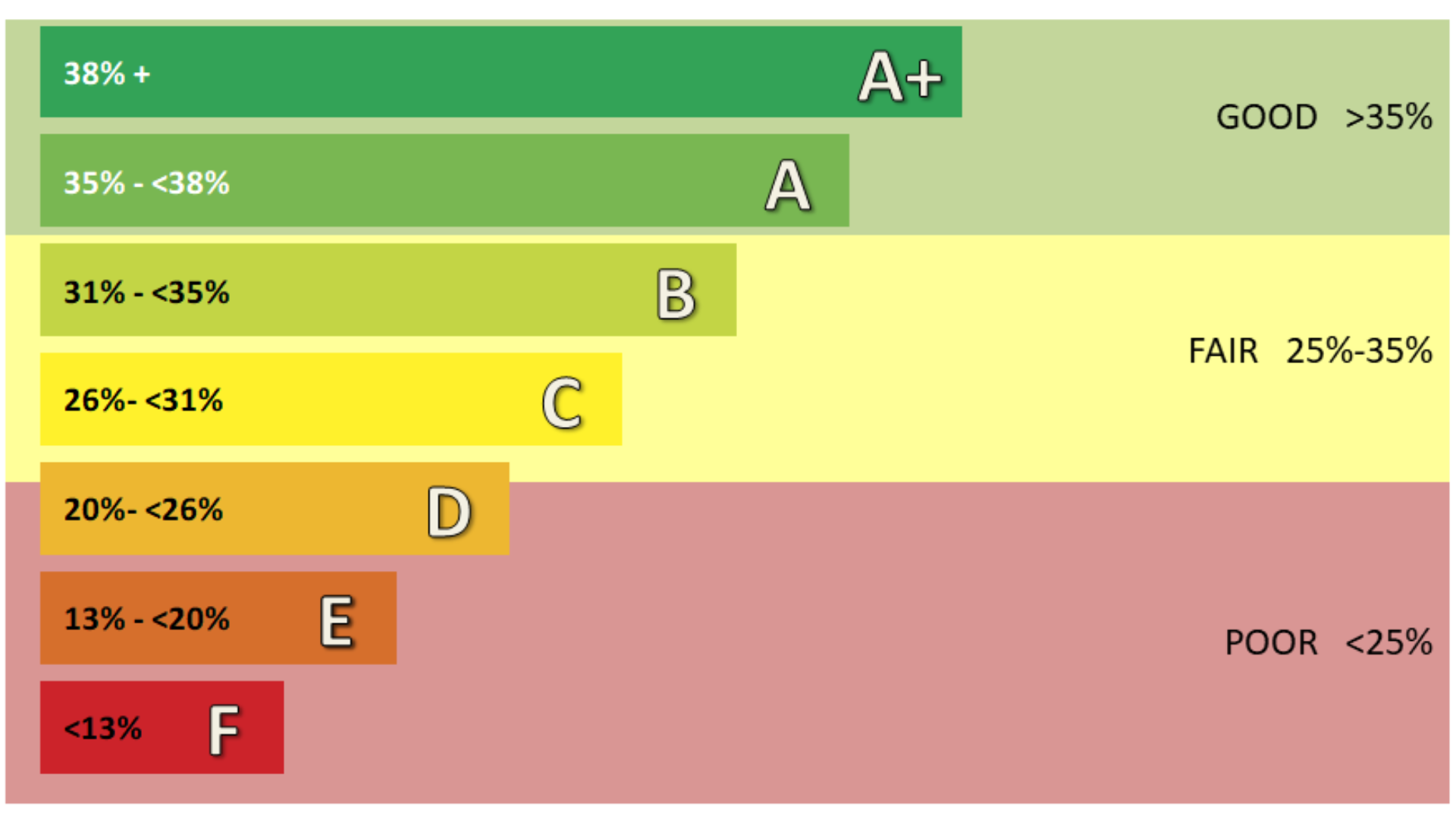

In space planning circles, the industry standard of a 35% teaching space utilisation rate is considered good, 25% – 35% is considered fair, and under 25% is considered poor. But have you ever tried explaining this to colleagues who don’t understand how such low figures can actually mean success?

Perhaps your current figure has sat in the ‘fair’ band for a number of years, and it looks to senior management like progress isn’t being made (when you know it is!)

The way we typically measure this rate doesn’t necessarily speak to the people we need to understand it, and that can be frustrating. Worse, a lack of understanding can end up putting you on the back foot when you’re trying to get management buy-in around key estate planning decisions.

The solution:

We really like this ‘energy ratings approach’ - developed by the Higher Education Space Management Group (HESMG) - that suggests a different way to measure teaching space utilisation rates and to get that all-important senior level understanding and buy-in.

HESMG’s approach explains space utilisation rates using an A to F-style rating, which you can see from the below provides a clear, visual representation of what success looks like. It also allows for movement within each of the traditional ‘good’, ‘fair’ and ‘poor’ bands, to more readily highlight when progress is being made.

HESMG’s approach explains space utilisation rates using an A to F-style rating, which you can see from the below provides a clear, visual representation of what success looks like. It also allows for movement within each of the traditional ‘good’, ‘fair’ and ‘poor’ bands, to more readily highlight when progress is being made.

“We used this for the first-time last year, and it was transformative to our reporting, because it meant something to people rather than presenting them with a sea of percentages”, says Kirsteen Williams, Head of Space and Timetabling at Anglia Ruskin University.

If you’d like to find out more about effective ways to measure your space utilisation rate – or need some help getting better management buy-in around estate planning decisions (or both!) get in touch – we’d love to help.

If you’d like to find out more about effective ways to measure your space utilisation rate – or need some help getting better management buy-in around estate planning decisions (or both!) get in touch – we’d love to help.

Challenge #2: Managing change

The challenge:

Managing change is a universal challenge felt by both space managers and timetablers. Changes to curriculums and teaching arrangements are an inevitable part of university life, but the challenge often lies in either a) too little advance warning being given or b) colleagues outside of estate planning and timetabling not understanding the impact that even small changes can make.

“We’ve experienced this recently”, explains Kay Green, Space & Strategy Manager at the University of Sheffield. “We’re in the process of changing from teaching in straight rows to a more collaborative style, which is fantastic, but then also requires more space. You’re trying to teach to the same number of students, but you need a bigger space to do it in. People (outside of estate planning) don’t always understand the impact of this.”

Managing change is a universal challenge felt by both space managers and timetablers. Changes to curriculums and teaching arrangements are an inevitable part of university life, but the challenge often lies in either a) too little advance warning being given or b) colleagues outside of estate planning and timetabling not understanding the impact that even small changes can make.

“We’ve experienced this recently”, explains Kay Green, Space & Strategy Manager at the University of Sheffield. “We’re in the process of changing from teaching in straight rows to a more collaborative style, which is fantastic, but then also requires more space. You’re trying to teach to the same number of students, but you need a bigger space to do it in. People (outside of estate planning) don’t always understand the impact of this.”

The solution:

It’s good practice as a space manager or timetabler to be involved at the design stage of any curriculum or course change. And this means making sure colleagues in your curriculum planning department are aware that the earlier you’re invited into the process, the better the end result will be.

Kay says that even the simplest of changes can take up to six months to get off the ground and through planning and design, and that this should be the timeframe to suggest when asking to be brought into conversations.

We know getting colleagues on-side in this way can sometimes feel like an uphill battle. Our Timetabling Basecamp Level 1 course can help lighten the load as it covers lots of ways you can increase collaboration across departments – so that timetabling and estate planning becomes smoother all-round.

It’s good practice as a space manager or timetabler to be involved at the design stage of any curriculum or course change. And this means making sure colleagues in your curriculum planning department are aware that the earlier you’re invited into the process, the better the end result will be.

Kay says that even the simplest of changes can take up to six months to get off the ground and through planning and design, and that this should be the timeframe to suggest when asking to be brought into conversations.

We know getting colleagues on-side in this way can sometimes feel like an uphill battle. Our Timetabling Basecamp Level 1 course can help lighten the load as it covers lots of ways you can increase collaboration across departments – so that timetabling and estate planning becomes smoother all-round.

Challenge #3: Planning around timetabling constraints

The challenge:

Every institution has to work within timetabling constraints – some are universal, others dependent on the unique make-up of your courses.

Universal timetabling constraints (or quirks, as we sometimes like to call them) might include:

Every institution has to work within timetabling constraints – some are universal, others dependent on the unique make-up of your courses.

Universal timetabling constraints (or quirks, as we sometimes like to call them) might include:

✔️Certain courses being advertised as running between set hours

✔️Giving students a break between every two hours of study

✔️Blocking out Wednesday afternoons for sports activities.

As a general rule, the more timetabling constraints you have, the harder it is to achieve a high space utilisation rate! But by challenging a few of the ‘traditional’ ways of doing things, we could ease the burden that they cause.

✔️Giving students a break between every two hours of study

✔️Blocking out Wednesday afternoons for sports activities.

As a general rule, the more timetabling constraints you have, the harder it is to achieve a high space utilisation rate! But by challenging a few of the ‘traditional’ ways of doing things, we could ease the burden that they cause.

The solution:

Dave Beavis, Strategic Space Manager at the University of Exeter believes a lot of universities shy away from making maximum use of the teaching hours available – which would go some way toward solving this problem.

“Often, very early and late slots go unscheduled. There’s a perception that the middle of the day matches people’s preferences. But I’ve carried out analysis on this and found no correlation between students turning up and the time of day,” he says.

He also points out that when teaching hours are extended there is an additional financial benefit too, because students tend to spend more time (and money!) using other on-campus facilities such as shops and cafes.

Kay agrees, saying there can be a tendency among universities to stick to the hours that we think will attract higher attendance rates, while losing sight of the fact that students are, essentially, paying customers who want to be on site.

“We provide an attractive environment they want to be in. (Offering 9 to 5 teaching hours) also prepares students for the outside world. It’s something we should all be more mindful of,” she says.

Sometimes there are good reasons to run teaching slots during set hours – for example if you’ve allocated a course to run between 10am and 3pm because your student demographic is mostly mature students with childcare commitments.

But it never hurts to take a close look at some of the more general timetabling constraints you plan around. If there is a tendency, for example, to shy away from using early or late slots, is there a specific reason – and could this be challenged?

Pro tip: some universities find income generating ways to fill ‘dead’ teaching slots and improve overall utilisation of space at the same time. Kirsteen says that at Anglia Ruskin University, they use Wednesday afternoon slots, for example, to book in conferences.

“This supports income generation alongside meeting teaching requirements,” she says.

Dave Beavis, Strategic Space Manager at the University of Exeter believes a lot of universities shy away from making maximum use of the teaching hours available – which would go some way toward solving this problem.

“Often, very early and late slots go unscheduled. There’s a perception that the middle of the day matches people’s preferences. But I’ve carried out analysis on this and found no correlation between students turning up and the time of day,” he says.

He also points out that when teaching hours are extended there is an additional financial benefit too, because students tend to spend more time (and money!) using other on-campus facilities such as shops and cafes.

Kay agrees, saying there can be a tendency among universities to stick to the hours that we think will attract higher attendance rates, while losing sight of the fact that students are, essentially, paying customers who want to be on site.

“We provide an attractive environment they want to be in. (Offering 9 to 5 teaching hours) also prepares students for the outside world. It’s something we should all be more mindful of,” she says.

Sometimes there are good reasons to run teaching slots during set hours – for example if you’ve allocated a course to run between 10am and 3pm because your student demographic is mostly mature students with childcare commitments.

But it never hurts to take a close look at some of the more general timetabling constraints you plan around. If there is a tendency, for example, to shy away from using early or late slots, is there a specific reason – and could this be challenged?

Pro tip: some universities find income generating ways to fill ‘dead’ teaching slots and improve overall utilisation of space at the same time. Kirsteen says that at Anglia Ruskin University, they use Wednesday afternoon slots, for example, to book in conferences.

“This supports income generation alongside meeting teaching requirements,” she says.

Challenge #4: Driving decisions with data

The challenge:

You have data and you’re not afraid to use it. Or are you? We're often surprised that when we're helping universities figure out their space planning challenges, that curriculum data sits in Word documents rather than in databases or Excel spreadsheets.

Then there’s your survey data. Traditionally, space surveys are carried out during allocated weeks, several times a year. This can mean that your overall utilisation score jumps up and down, rather than building a consistent picture that accounts for all trends over the course of an academic year.

You have data and you’re not afraid to use it. Or are you? We're often surprised that when we're helping universities figure out their space planning challenges, that curriculum data sits in Word documents rather than in databases or Excel spreadsheets.

Then there’s your survey data. Traditionally, space surveys are carried out during allocated weeks, several times a year. This can mean that your overall utilisation score jumps up and down, rather than building a consistent picture that accounts for all trends over the course of an academic year.

The solution:

Good data at the curriculum design stage – that determines activity types, contact hours, and space types that’ll be needed – can inform effective estate decisions much earlier in the process. And it should always be stored in spreadsheets or within an internal database, where it can sit centrally and mix with other data sets to help you work out your space needs.

“When your data sits within a database, you can even build in future predicted student numbers and test different scenarios, to understand the impact of curriculum changes and more accurately determine whether you actually have enough space to accommodate course delivery,” suggests our Director, Ben Moreland.

And when it comes to carrying out surveys, advancements in technology now give us more opportunity to carry out real-time audits all of the time – with some universities now experimenting with the use of heat sensors, pressure sensors on chairs and even Bluetooth location data to build a more holistic and accurate picture of space use across campus.

“We have live space utilisation data that’s available via a suite of reports, that anybody can access and that’s useful when faculty departments are planning for any additional space requirements,” says Kirsteen.

“This also means our space is highly visible and that we can have an ongoing discussion around how it’s used,” she adds.

If you need help getting your space utilisation data in order or carrying out a survey, we can help.

Good data at the curriculum design stage – that determines activity types, contact hours, and space types that’ll be needed – can inform effective estate decisions much earlier in the process. And it should always be stored in spreadsheets or within an internal database, where it can sit centrally and mix with other data sets to help you work out your space needs.

“When your data sits within a database, you can even build in future predicted student numbers and test different scenarios, to understand the impact of curriculum changes and more accurately determine whether you actually have enough space to accommodate course delivery,” suggests our Director, Ben Moreland.

And when it comes to carrying out surveys, advancements in technology now give us more opportunity to carry out real-time audits all of the time – with some universities now experimenting with the use of heat sensors, pressure sensors on chairs and even Bluetooth location data to build a more holistic and accurate picture of space use across campus.

“We have live space utilisation data that’s available via a suite of reports, that anybody can access and that’s useful when faculty departments are planning for any additional space requirements,” says Kirsteen.

“This also means our space is highly visible and that we can have an ongoing discussion around how it’s used,” she adds.

If you need help getting your space utilisation data in order or carrying out a survey, we can help.

Summary

We’ve whizzed through these four challenges that we know lots of you working in space and estate planning face, and we hope our solutions have given you some food for thought.

And if they are challenges you recognise within your own institution, come and have a chat about how we can help you to solve them.